Sacred chapel table, and lighted glass from above, reappear in new Amistad Conference Room

Part of a sacred table from the United Church of Christ’s recently closed Cleveland chapel is back. So is some of the translucent glass that hovered above it.

They appear in new forms in the UCC’s recently opened new offices, a half-mile from their old home. They’re embedded in a table and an overhead lighting array in the Amistad Conference Room.

They embody the spirit of continuity, said the Rev. Traci Blackmon, who headed a design team for the new UCC office floor at 1300 East 9th Street. As they did in the chapel, the table and glass will remind staff and visitors of the ongoing work of liberation — and, in the words of the current UCC vision statement, “a just world for all.”

“The Amistad story is our story,” Blackmon said. “In that 1839 rebellion, captives fought their captors and won freedom. They found allies in their long legal battle. Their self-liberation, with God’s help, was a spiritual act.

“Now we will continue to gather around a table that reminds us of that story. It is made of African wood and illuminated from above — tangible, visible reminders that our work is sacred. And it is ongoing. The struggle did not start with us, and it will not end with us.”

The transfer of the items from the chapel — and the table’s transformation — are themselves a story of care, planning and artistic design.

Early vision

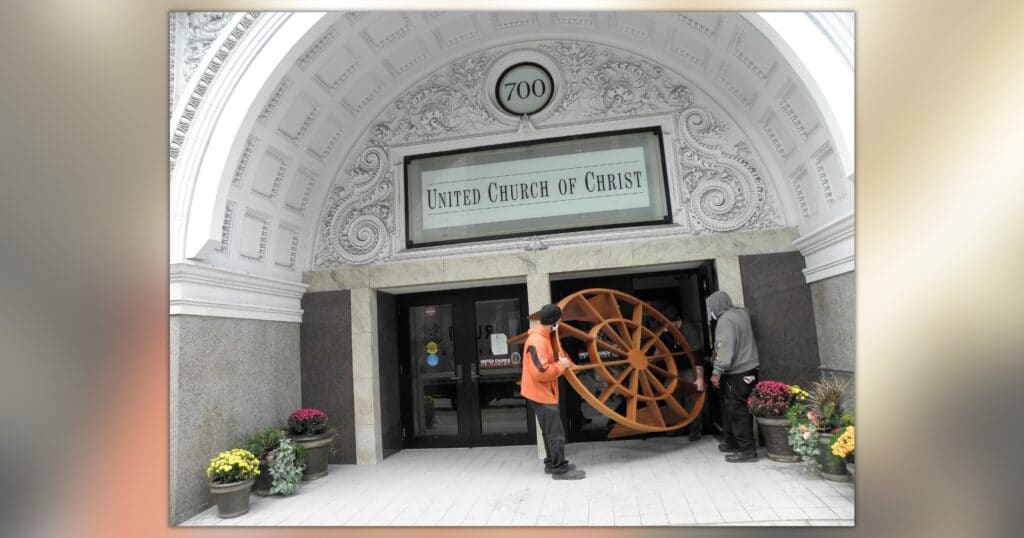

The property at 700 Prospect Avenue, past home of the Amistad Chapel and the UCC’s national offices, transferred to a new owner on May 31. Months before that, Blackmon was already pondering how to incorporate items from the chapel into the design of the UCC’s new leased space.

The problem was how. There would be spaces for meditation and prayer on the new office floor. But none of them would approach the size of the Amistad Chapel, which took up half the ground floor at the old Church House.

When she struck upon the Amistad Conference Room as the solution, she took action to preserve the chapel’s two central features.

Glass, in sections

Removing the overhead glass from the chapel was one thing.

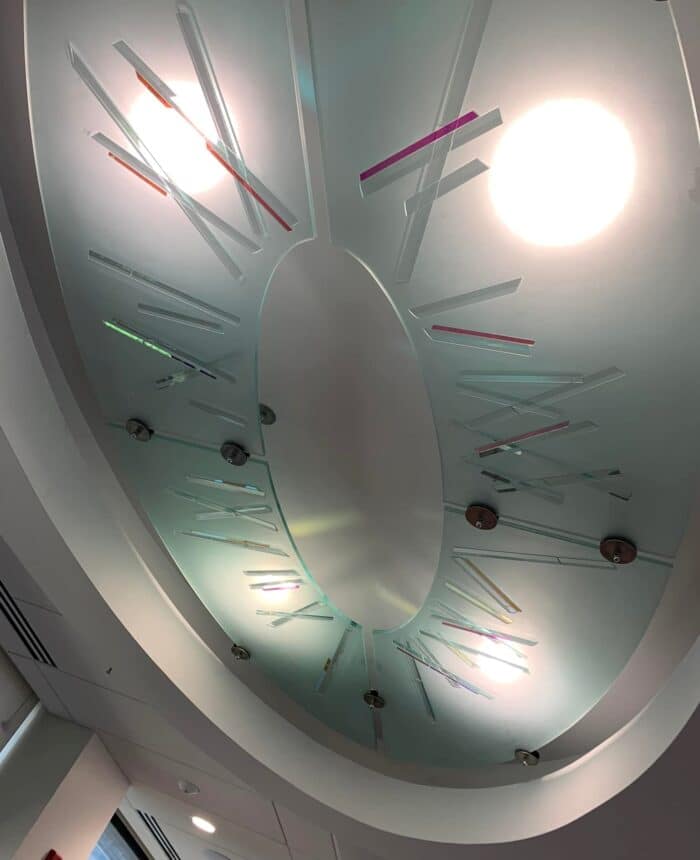

There was room at the new place for just the center oval of a larger array, known in architectural terms as a baldacchino etched with dichroic glass prisms.

That limit turned out to be a good thing.

It took a contractor painstaking hours to dislodge that one oval, carefully and in sections, from its well-anchored place in the ceiling. The glass was then stored for weeks until it could be hung in the new conference room in June. (The rest of the baldachhino remains hanging in the former chapel. The building’s new owner has not decided whether it will be part of new retail space there.)

‘This is different’

Preserving and transforming the table was another matter entirely.

For that project, Blackmon enlisted Rustbelt Reclamation, whose urban workshop is just two miles from the old 700 Prospect Avenue Church House.

The craftspeople at Rustbelt, a woman-owned firm, specialize in furniture. They do custom work only. And they do it for clients all over the world.

But they had never taken on a project quite like this.

“We have worked with salvaged pieces before, but they were always things we had gone out and found,” said Rustbelt President Megan November. “This is different. It’s an existing — and such a particularly symbolic — piece.” She said it invited “more preservation than repurposing.”

Symbolism and sacred wood

Indeed, the table’s sacred and symbolic dimensions were many. Spokes like a ship’s wheel and legs like rudders were just two of them. For two decades, the chapel reminded worshipers and Church House visitors of that 1839 rebellion. Captives aboard the schooner La Amistad mutinied against human traffickers. Ancestors of today’s UCC came to their aid in their freedom fight.

A connection to that story was literally built into the table. It was made of Iroko wood from West Africa, the captives’ homeland. Traditional cultures there believe Iroko has healing properties.

And that was only part of the multilayered symbolism of the room, said architect and UCC member Jefferson Riley, whose Connecticut firm, Centerbrook, designed the chapel. As just one example, he said, the table was divided into 12 sections, recalling Jesus’ 12 disciples.

How could it fit?

And then there were the decades of memories formed around the table. During the chapel’s dedication in 2000, it held vessels for the African tradition of water libations, poured in honor of ancestors. Over the years, it held not only the Bible and Communion elements but also crosses, flowers and symbolic objects of all kinds, placed there by worship leaders for:

- Weekly staff services and occasional all-staff gatherings.

- Meetings of UCC groups and governing bodies.

- Memorial services.

- Ecumenical and social-justice gatherings.

And for many years, a local congregation, Amistad Chapel UCC, gathered around the table for services on Sunday mornings.

How could the table — built especially for the chapel’s large dimensions — fit into the new office design?

At the center again

Blackmon brought that challenge to Rustbelt Reclamation. Together, she and they found a way to preserve part of the table as a different kind of gathering place.

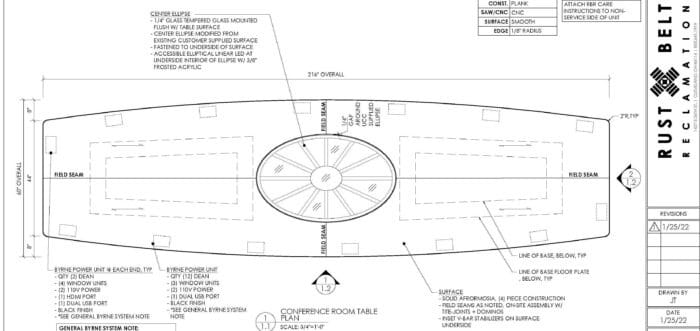

The table’s inner oval would be embedded in a much larger conference table.

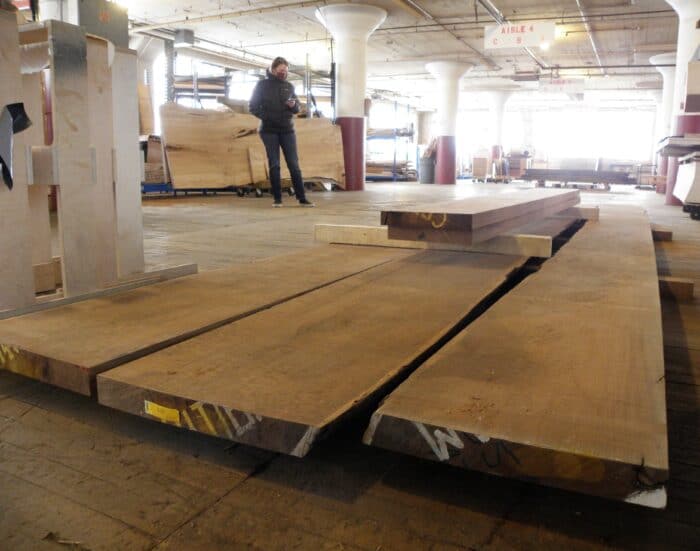

The Rustbelt Artisans were impressed by the historic theme as they began to envision the project. They sought African wood for the entire conference table. For reasons including supply and expense, “we were looking for an alternative to Iroko,” said Rustbelt Vice President Grayson Glass.

From the Democratic Republic of the Congo they were able to get a shipment of a similar wood, Afromosia, that the firm has worked with on other recent projects. Sometimes called African teak, “it’s the color that everyone wants,” he said — and it’s a good match for the chapel table’s hue. He said they felt lucky to get four boards big enough for the project. The new table is 18 feet long and 30 inches across at its widest point.

‘Visual drama’

The conference table has contemporary aspects. Wiring through each of its two bases feed USB, HDMI and power outlets — enough of them to be shared by the 14 people the table can seat. Its wood has polyurethane topcoat and sealer for durability, November said.

But its central feature are the wooden spokes that were once at the very center of the chapel. They are illuminated under the table’s glass top as well as from the oval of ceiling lights.

Interior illumination was the idea of Rustbelt Director of Operations Christoph Schoenlein. He said gradient LEDs, mounted inside the table, will add “visual drama” to accent the UCC’s heritage.

Rustbelt also built an 8-foot credenza for the conference room, also of Afromosia.

The legs and outer oval of the chapel table are not part of the conference table. But they, too, will live on a in a new form. Blackmon said she will share that surprise later this summer.

‘A real story to it’

Careful handling of the chapel table started back on Nov. 3, 2021, when Rustbelt’s Nick Sekura and Max Queen arrived at 700 Prospect to move it. They soon learned it wouldn’t fit through the Church House front doors. At length, they got it out to the moving truck — after they carefully took off four table legs and UCC Maintenance Supervisor John Grimes removed a door post.

After extensive design and drafting work in consultation with Blackmon, the Rustbelt staff then worked on the table from March to June at the company shop. They built it, then took it apart, then delivered and reassembled it in the UCC executive conference room. It was among the last things delivered to the new offices, November said, to avoid construction hazards such as hammers, paint and dust.

While awaiting work, it rested — securely padded and covered — on a rolling cart in the same Rustbelt shop that generates high-end furniture for hotels, resorts, law firms, sports venues, corporate offices and private homes.

And as much as the craftspeople there love all of their work, this project was “more exciting than designing a bar for a ballpark,” November said. Their work is especially satisfying, she said, “when there’s more to it, when there’s a real story to it.” And they were glad to contribute to a Cleveland project, “in our backyard.”

Content on ucc.org is copyrighted by the National Setting of the United Church of Christ and may be only shared according to the guidelines outlined here.

Related News

Send a prayer shawl along to General Synod 35

There’s been a buzz about Missouri, Kansas – can you hear it? It’s more of a clicking...

Read MoreOpinion: UCC pastor and former Institute of Peace Staffer calls for action in defense of peace

Editor’s Note: The United States Institute of Peace (USIP), an independent institute founded...

Read MorePension Boards appoints David A. Klassen as its President, CEO

The Pension Boards, an affiliated ministry of the United Church of Christ recently announced its...

Read More