Wildfires, freeways, smokestacks: Central Atlantic Conference tackles air quality in communities of color

This summer, the United States experienced some of the worst days for wildfire pollution in recorded history.

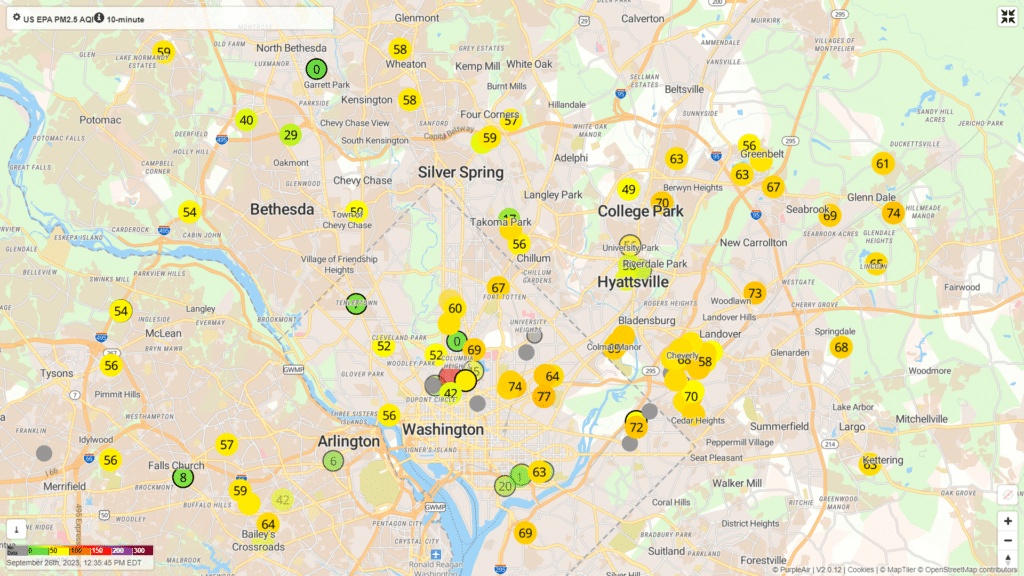

Around the same time, the Central Atlantic Conference of the United Church of Christ was installing air quality monitors at its churches across the “DMV” region of Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia.

As partners in a project called the Mid-Atlantic Data Justice Collaborative, the CAC Justice and Witness Action Network began recruiting churches to help provide high-quality data on air quality. The aim is to use hard data to support what many have experienced: that communities of color have been systematically disadvantaged and burdened with environmental degradation and pollution.

“It was only a couple of weeks after we started putting them up on the churches that we got all the dangerous air quality alerts for the wildfires,” said John Kasander, who served as organizer of the project as part of his field education at Lancaster Theological Seminary. “It’s a sort of invisible threat that it can be hard to understand why it’s important and why you should care, and this got people’s attention.”

‘Part of a larger whole’

The Mid-Atlantic Data Justice Collaborative is seeking that attention to create policy change for environmental justice. The partnership between the CAC, Interfaith Power & Light (DC.MD.NoVA) and the University of Maryland’s Center for Community Engagement, Environmental Justice and Health (CEEJH) is focused on developing a grassroots air quality-monitoring network by installing monitors on the buildings of UCC and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches in the DMV region.

The UCC and AME are each on their way toward recruiting 50 churches to participate.

“Environmental racism — the manifestation of intentional urban planning choices — has led to sweeping disparities in quality and duration of life for communities of color who too often find themselves living next to smokestacks, freeways and water treatment plants. Our work is bound up in achieving equity for these communities,” the project’s description reads.

This project is one way for CAC to prioritize collective engagement of environmental justice, beyond each church’s carbon footprint and their own facilities, according to the Rev. Marvin Silver, director of the Justice and Witness Action Network and CAC Associate Conference Minister.

“Many churches in our Conference work on the environment and climate at some level, but many never imagined what it would be if we as the UCC in this region came together collectively and prioritized an issue in this area and together try to have an impact,” said Silver. “That’s our mantra as we work with our churches. It’s important to see ourselves not as an isolated unit or entity, but to see the role we can play as part of a larger whole. Then we can contribute to the process of bringing about a transformative impact and creating lasting change around issues that we care about.”

Silver points to the example of laws limiting bus idling in Washington, D.C., which have had a significant impact on the air quality and quality of life for people in the D.C. area in recent years.

Grasping the impact

Kasander has spent a lot of time on church roofs assisting CEEJH staff with locating a solid spot with good airflow to install monitors.

He previously lived in Baltimore on a street with heavy bus traffic and near Interstate 83, a highway that cuts through the city.

“When we first moved in, the front windows were caked with exhaust,” he said. “We destroyed a couple of dish towels cleaning the windows, and within a few weeks, they were sooty again.”

When he moved to a different location, his asthma improved. This gave him what he described as a “folk understanding” of air quality.

“I didn’t grasp how serious of a problem it was until I started getting involved in this program,” he said. “I also didn’t understand the racial character of pollution. A past UCC report shows that people of color are more likely to live near three to four toxic pollution industries. We place these things in places where people are viewed as expendable by policy makers.”

‘Educating church leaders’

As part of the Mid-Atlantic Data Justice Collaborative, Kasander has worked to get UCC churches invested in being part of the solution by hosting the air quality monitors on their buildings. To participate, he said, churches just needed an outlet, Wi-Fi and someone from the congregation identified as a point person.

Beyond agreeing to host the monitor, the churches bear no responsibility for them. CEEJH installs small, inconspicuous PurpleAir monitors with zip ties to prevent any impact to buildings, collects data and creates reports to be shared with the churches and decision makers around public policy. Data from the monitors is publicly accessible.

CAC churches were also invited to a series of virtual workshops in late 2022 covering the role of community scientists and using air quality data for policy change.

“We were intentional about not just installing monitors, but educating church leaders on issues of air quality in and around poor and POC (people of color) communities — and connecting that to our work of community organizing and justice action,” Silver said.

Participating churches received a $500 grant to put toward environmental justice programming — a model that Kasander said encourages congregations to pursue an issue important to them.

Silver says that while the majority of participating UCC churches are in more affluent, Euro-descendant communities, it’s important to collect data that can show policymakers the contrast between these and the lower-income communities of color also being monitored.

‘Can’t afford to stay silent’

The air quality project’s organizers, including Silver, presented a panel discussion at a CEEJH symposium on environmental justice and health disparities Sept. 15.

Arielle Wharton, CEEJH staff and project manager, described the severity of air quality issues that the project seeks to address.

“Particulate matter poses severe health risks, including cardiovascular disease, reduced lung function, increased asthma rates, emergency room visits, diabetes and higher overall mobility and mortality rates,” she said. “This project’s significance lies in its community-based approach to collecting detailed neighborhood-level air pollution data, addressing a critical data gap that has hindered informed action for too long.”

While the project is long-term and will collect data through multiple seasons, Kasander noted the importance of congregations getting engaged in advocacy work to address these issues now and in the future.

“This is our opportunity to get involved as community in addressing injustices being done, figuring out what’s causing early deaths and less pleasant lives, and compelling governments and private entities who bear responsibility to change that behavior,” he said. “We have taken notice this is going on, and we can’t afford to stay silent anymore.

“These are systemic and structural problems that we’re going to have to address, and we’re going to have to address it as a collective. And that’s what the church is there for: to see a wrong and right it.”

Content on ucc.org is copyrighted by the National Setting of the United Church of Christ and may be only shared according to the guidelines outlined here.

Related News

UCC to offer Election Day Prayer Service and Vigil

On Election Day, Nov. 5, join the Rev. Karen Georgia A. Thompson together with United Church...

Read MoreGoing beyond the blessing: Churches emulate St. Francis’ care for animals

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lu3LYwhLxCo UCC News presents a video news story on the...

Read MoreUCC leaders invite all to global celebration of Reformation Sunday

This Reformation Sunday, leaders from the United Church of Christ will participate in a global...

Read More