UCC is front and center as U.S. creates new office linking environmental and racial justice

The U.S. government just formed a federal office to focus on environmental justice and civil rights. The United Church of Christ was there at its creation — and in the 40-year movement that led to it.

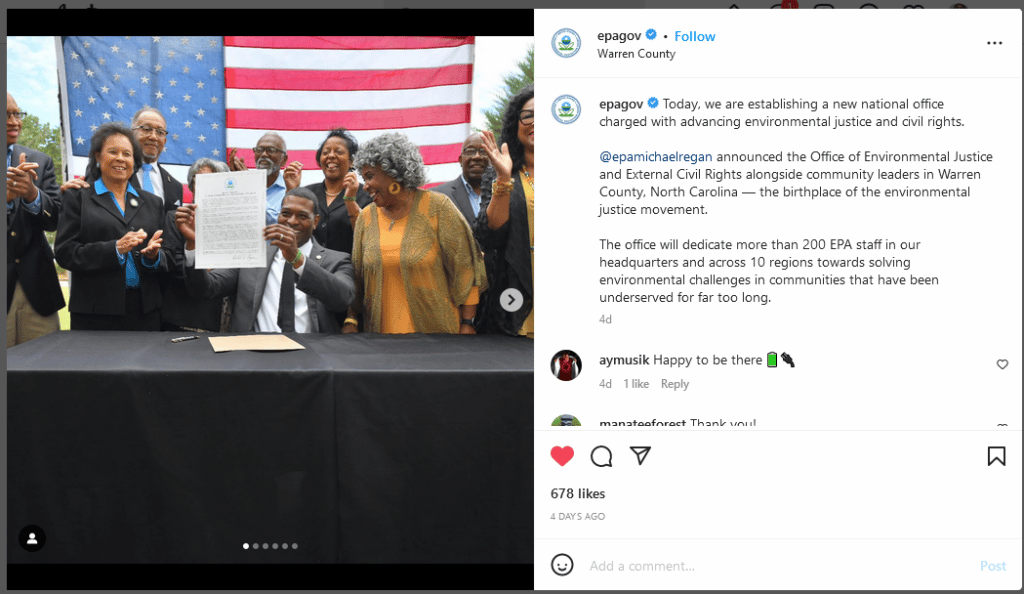

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan signed the new office into existence in a Sept. 24 ceremony at the Warren County, N.C., courthouse. It’s the predominantly Black county where a fight against the dumping of toxic chemicals in a landfill in 1982 ignited what is now a global movement for environmental justice.

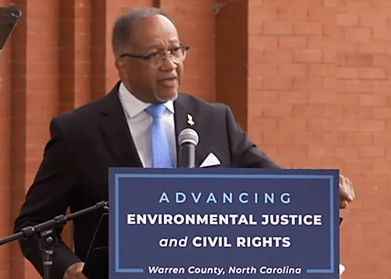

Two key UCC leaders of those original protests spoke at the Saturday ceremony: Dollie Burwell, a member of Oak Level UCC, Manson, N.C., and the Rev. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., who went on to lead the UCC’s Commission for Racial Justice.

They praised the new Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights and its mission of, as Regan put it, “ensuring that all people, no matter the color of their skin, how much money they have in their pocket, or the community that they live in, realize the full protections of environmental laws.”

Sacrifice and legacy

The ceremony was a highlight of some two weeks of observances of the 40th anniversary of the toxic-dumping protests, which started in September 1982 and lasted six weeks.

Burwell, often described as the mother of the environmental justice movement, recalled “all of the courageous and dedicated women, men and children of all races who participated in our struggle.” She recalled their marches “to the site of the landfill, blocking the trucks filled with PCB-laced soil – with hundreds, over 500 to be exact, being arrested and jailed.” PCB stands for polychlorinated biphenyls, a cancer-causing chemical.

And she remembered many allies. “Individuals served as bail bondsmen,” she said. “Women cooked and fed the protestors. Preachers, elders and other prayed daily and sometimes hourly for our safety. We received numerous other ordinary people, performing numerous other tasks. We remained committed to (opposing) this PCB dump until it was cleaned up and detoxified by the federal and state governments in 2004.”

She thanked the Biden administration and the EPA “for their commitment and investment in environmental justice.”

“We are very, very grateful, Administrator Regan, that you chose Warren County to make this announcement today. To us, you have acknowledged and recognized the work, the tremendous sacrifices and the legacy of Warren County citizens and the many leaders across this country who started the environmental justice movement and who continue to fight for environmental justice.”

‘Still going on’

Chavis, who, like Burwell, was among those arrested in 1982, affirmed what she and other speakers had described about the protests. The movement has since gone global, he said, because the problem is global and environmental racism is still real. He said the burden of everything from climate breakdown to bad drinking water still hits people of color hardest.

“What happened in this county 40 years ago is still going on – in North Carolina, in Alabama, in Louisiana, in Mississippi, but also in Michigan, in Minnesota, in California, in Texas,” he said. “I could call all the 50 states, but can’t stop there. It’s going on in Brazil. It’s going on in Africa. It’s going on in the Caribbean. It’s going on all over God’s Earth.”

“Now we’re bringing a brother up who’s presenting some solutions,” said Chavis in his introduction of Regan. Chavis noted that Regan himself comes from Goldsboro, N.C., an area with similar struggles with poverty and racism. “Thank God that Michael Regan is the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency at a time when we’re going to not only connect Civil Rights and environmental justice but provide solutions to the problems that we face in this nation and around the world.”

‘Unrelenting advocacy’

Regan, in a speech before sitting down to sign the office’s formative document, honored the “giants of the environmental justice and Civil Rights movement” present.

“I was just a child when the state decided to site the PCB landfill in the backyard of a predominantly Black community,” Regan said. “But I remember my parents discussing the heroism of the women and men who locked arms and lay down in front of those trucks.” He named Chavis and Burwell among them.

“These visionary women and men sparked something so much bigger, so much more powerful,” he said. “And that’s what we’re here today to honor and to uplift. The reason we’ve reached this moment, this moment when environmental justice is front and center to President Biden’s agenda and EPA’s agenda, is because of the unrelenting advocacy of so many of you here today.”

Today’s environmental racism

Regan said he had witnessed today’s environmental injustices on his recent “Journey to Justice” tour to various U.S. regions. In poor and people-of-color communities, he had seen “deeply troubling” conditions, including “students using porta-potties because of failing water infrastructure,” “generations of families living in the shadows of petrochemical facilities,” and children playing near open sewage in the yards of their homes.

“These communities show us that the fights for Civil Rights and environmental justice are inseparable — for health justice, for racial justice, for economic justice, for climate justice,” Regan said. “We cannot be for one without being for the other.”

The new office within the EPA — using support from this year’s bipartisan infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act — will be dedicated to “finally ensuring that communities that have long borne the burden of pollution see, breathe and feel the benefits of the federal government’s investments,” he said.

‘Essential work’

Regan said the new office will have 200 staff members and a budget of $3 billion. It will, among other things, administer “environmental justice grants.” These, he said, will benefit “communities who have not had access, who haven’t had a seat at the table, who haven’t had the infrastructure in place to apply for these dollars, and who have been underserved for far too long.”

He said the new office is structurally built to last. “It will memorialize the agency’s commitment to delivering justice and equity for all, ensuring that no matter who sits in the Oval Office, or no matter who heads EPA, this work will continue long beyond all of us to be at the forefront and the center of everything this agency does.”

“This is essential work,” Regan said. “It’s the work that I came to this administration to do and it’s the work that you all have been demanding for generations.”

‘Lasting change’

“We are witnessing an important lesson on how social change happens,” said the Rev. Brooks Berndt, the UCC’s minister of environmental justice, who attended several of the 40th-anniversary commemorative events. “Prophetic public actions can have unforeseen impacts as ripples become waves, as voices from the margins become amplified until they reverberate in the halls of power.

“We are witnessing a profound level of institutional change that is elevating environmental justice to a core part of the EPA’s mission, not just in word, but, crucially, in the staffing and funding that signal the high priority it has become. This is lasting change that no future administration could easily undo.”

“Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. told us the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Burwell said. “In 1982, in Warren County, we bent the arc.”

She said she hoped the new office “will yield great fruit, and that this community and other communities throughout this nation will be able to accomplish more of their environmental-justice goals, such as culturally sensitive environmental health studies. And it will enable all of us to continue to bend the arc toward environmental justice.”

Content on ucc.org is copyrighted by the National Setting of the United Church of Christ and may be only shared according to the guidelines outlined here.

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More