Harm reduction ministries welcome drug users, save lives

People who use drugs may not come to mind immediately when United Church of Christ members think of values like Extravagant Welcome or Love of Neighbor. A growing community of UCC people is working to change that.

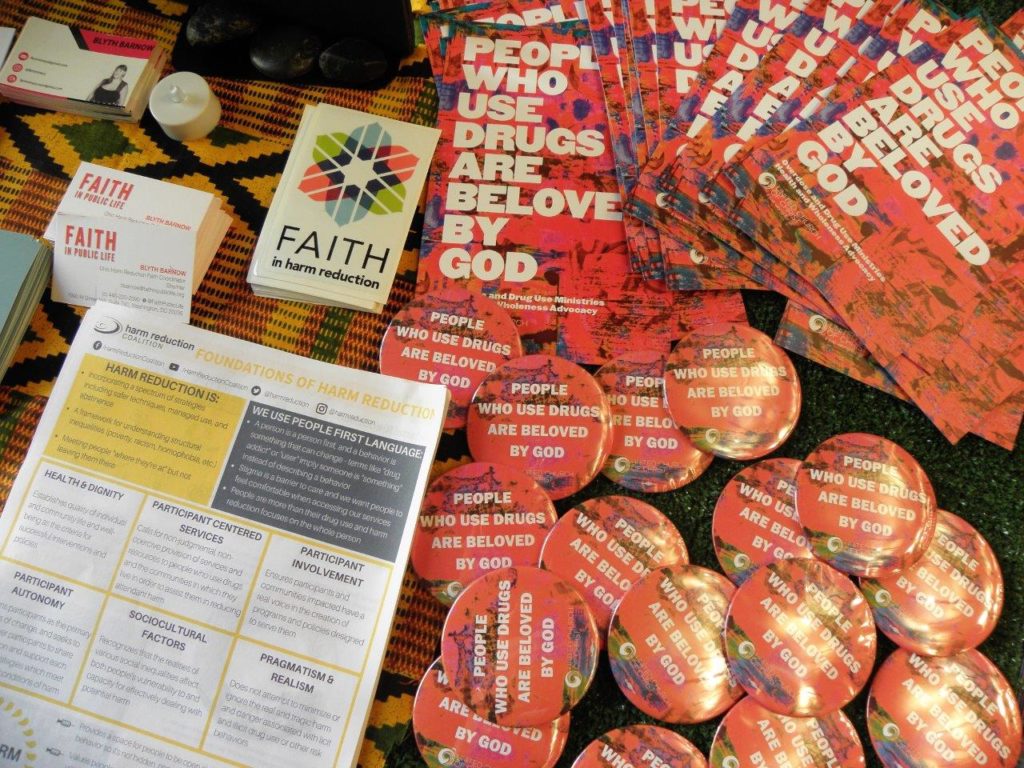

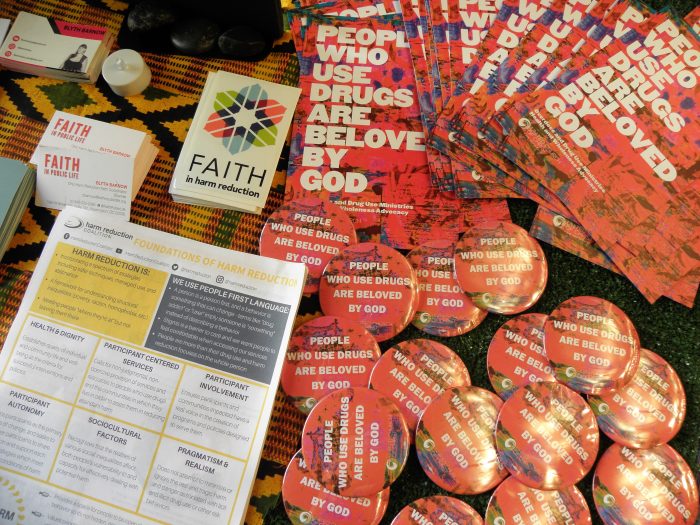

In worship services and at a 2019 General Synod exhibit, they have blessed naloxone, or Narcan, which counters the effects of an opioid overdose, and trained people to use it. They have decorated needle receptacles in a local church. They have made buttons that say, “People who use drugs are beloved by God.”

This harm reduction movement centers around an urge to eliminate the stigma surrounding opioid and other addictions, to help churches talk about drugs, and to recognize that people who use them have wisdom to share about saving lives and building community, whether they are able to abstain or not.

“A core value of this effort from the very beginning has been to center the voices of those with lived experience,” said Mike Schuenemeyer, Executive for Health and Wholeness Advocacy Ministries in the national setting of the UCC.

‘They do not need our pity or condemnation’

A leader of the movement is Blyth Barnow, a Pacific School of Religion graduate who speaks and teaches about harm reduction all over the country and is pursuing ordination in the UCC. She helped run the Synod workshop and exhibit space, where, she said, “we distributed over 300 naloxone kits – we ran out – trained more people than that, and gave out 450 of those buttons.” She wrote a “Naloxone Saves” worship service that has been used in UCC churches around the country, including the Amistad Chapel in Cleveland on Sunday, Aug. 25. Her work even informed an overdose victim’s funeral this summer.

“I have known in my gut for a long time that the church has wanted and needed a space to talk about substance use in this way,” Barnow said. “Synod really confirmed that. I didn’t really anticipate how it would feel for me to walk around Synod and see people I didn’t know wearing the buttons, or to see how touched people were to engage with ministers in their church around substance abuse, knowing that abstinence is not always possible or where people are at yet. It was deeply meaningful.”

Related ministries, such as syringe exchanges, started as early as the 1980s in response to the AIDS epidemic, and some congregations and ministers have been promoting harm reduction more recently. “What felt different to me at Synod was to have a denomination step in and say, ‘We need to be talking about substance use through a harm-reduction lens,'” Barnow said.

Barnow got involved partly because she lost a partner to overdose 15 years ago. But for her, it’s more than personal. It’s systemic, and it connects with other justice issues the UCC cares about, including racism. Her teaching delves into America’s long history of “racialized drug policies,” ranging from the targeting of Chinese migrants in past centuries to today’s disproportionate sentencing of African American and Latinx people while white people use drugs at the same rate. “Today, the administration is leveraging overdose deaths to push the dehumanizing immigration policies we see at the border,” she said.

Instead of demonizing them, harm-reduction principles encourage churches to learn from people who use drugs, who themselves are the people who prevent the most overdose deaths. “Even in the midst of this current overdose crisis, people who use drugs are focused on building community and practicing safety,” Barnow said. “It’s about resurrecting our communities and our sense of hope. These issues that we’re facing are fixable. People who use drugs are showing us the way forward. We just need to listen. Not only do they not need our pity or condemnation, they deserve our thanks.”

‘Made in the image of all that is good’

In churches, “drug use is an issue that people are dealing with, but folks are having a hard time articulating it,” said Erica Poellot, another leader of the movement. This can be true even in churches that are progressive on many other issues, like New York City’s Judson Memorial Church, where she directs its Faith and Harm Reduction program, which is part of the national Harm Reduction Coalition. She, too, speaks around New York City and nationally on harm reduction and helped lead the Synod workshop and exhibit activities.

Judson, affiliated with the UCC, the American Baptist Churches and the Alliance of Baptists, had a breakthrough when harm reduction was the topic of a 2017 sermon. “People had never heard drug-related issues talked about in a sacred space in that way,” Poellot said. “All of a sudden we started hearing stories: a woman whose adult children were incarcerated in other states; she had never thought she was able to bring that into the church. A young man who was having trouble accessing help here locally. We’d been making safe injection kits and safe sex kits for years, but the universal thing we began to hear was that people don’t know how to talk about drug use.”

In part through connecting with a local harm reduction agency and drug users’ union, Judson is now more comfortable with a visible ministry with people who use drugs, overtly welcoming them to a monthly Agape Supper, for example, and including them in its leadership. Judson even overcame an initial discomfort about having safe disposal containers for syringes in the church building and wound up decorating them.

Poellot, herself in recovery through 12-Step programs, sees value in Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Heroin Anonymous and other similar programs that many churches host. A particular value of harm reduction is that it counteracts messages that society and the church have sent for too long. “The core of this is that we have dehumanized folks who use drugs, instead of recognizing them as made in the image of all that is good,” she said.

What churches can do

Many churches could help by just considering the messages they send, said Peggy Matteson, Commissioned Minister of Congregational Health with the Rhode Island Conference of the UCC. Language can stigmatize people in congregations who use drugs or have family members who do.

The stigma is similar to the shame sometimes attached to mental illness. “How many people are walking around with depression but are not asking for help because they are ashamed to?” Matteson said. “There are people who are addicted to opioids and can’t go off them. The drug has become a vital part of their ability to function, but they can’t tell anybody.” A friend of hers, for example, was rear-ended by a drunk driver 20 years ago. Pain management for her severe injuries includes a steady level of legally prescribed. Neither she nor other drug users deserve stigma, Matteson said.

Matteson and her colleagues in the UCC’s national Wellness Ministries and Faith Community Nurse Network offer resources for churches that want to do better. She especially recommends the Opioid Epidemic Practical Tookit from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A family member’s experience using naloxone to save people from overdoses motivated Alan Stivers of First Congregational UCC, Palo Alto, Calif., to get involved. His in-law in Ohio, saved the lives on one person in the big-box store where she works as a security manager, another in the store parking lot, and one more at – of all places – a medical school commencement. “When people are OD’ing at a medical school graduation, something’s really off the rails,” Stivers said.

Stivers said a friend who runs large county health programs in California told him, “The most important factor is whether the recovering addict has a stigma-free relationship with someone who can help them get through.” “I thought that would be a good role for congregations of the UCC,” Stivers said. After conversations with national staff members, Stivers and his wife, Carole, contributed financially to the Synod workshop and exhibit, and seed money for the nascent Overdose and Drug Use Ministries work of the UCC’s Health and Wholeness Ministries.

Graves, the Minnesota pastor, recalled “two very young people from a rural farming community coming by the Synod booth and lighting up at the thought that this was even something that existed – talking to people who could hear their truth.”

“We cannot underestimate how much people need these resources,” Graves said. “Anything we do that magnifies and empowers the way we can love one another, that is the work of God and the work of Christ in the world.”

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More