Valerie Russell lecturer shares ‘truth, hidden in plain sight’

It was a phrase that Dr. Joy DeGruy came back to again and again while delivering the Valerie Russell Lecture to General Synod on July 17: “the truth, hidden in plain sight.”

DeGruy, a nationally and internationally renowned researcher and educator whose research focuses on the intersection of racism, trauma, violence, and American chattel slavery, spent close to an hour talking about various familiar narratives in history and in culture – which, when examined more closely, are filled with contradictions.

A culture of contradictions

DeGruy talked about growing up with only white characters on television, and how that led her to assume that the “whole world was white.” This, despite the fact that the majority of people on the planet are people of color. Of the 7.8 billion people living on earth, nearly 60 percent are in Asia. Another 17 percent are African. Less than 10 percent are European, and less than 5 percent are in North America, she said.

These numbers create a “pathological fear” for people of European descent.

“America’s pathology is her denial. It’s her secrets that make her sick,” she said.

As another example, DeGruy bought up what most schoolchildren learn about continents: that there are seven: Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Antartica and Australia. But, she said – the definition of a continent is a large body of land surrounded by water.

Why then, she asked, was Europe ever considered a continent? One online site, InfoPlease, explains: “political considerations have often overridden geographical facts when it came to naming continents.”

In other words, DeGruy said, politics were considered more important than the truth.

DeGruy pointed to the U.S. Constitution as the “most flagrant, glaring contradiction that we have in front of us.”

‘Less than human’

DeGruy questioned how the country on the one hand could say “We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, …” while at the same time it was “committing genocide against Indigenous native people and enslaved people of African descent, something that lasted 339 years at least.”

“How do we resolve the dissonance – the anxiety that results from simultaneously holding contradictory or otherwise incompatible attitudes?” she asked.

The country resolved that, she said, by defining black and indigenous people as less than human. She quoted the Dred Scott decision of 1857, in which the chief justice said slaves were not intended to be included under the “We the People” clause because they were, he said, “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

“This describes America’s current state better than any. It helps you understand George Floyd’s plight,” she said. “You see, the man with his knee on the neck, he felt like this was not even a human being.”

No chains, no connection

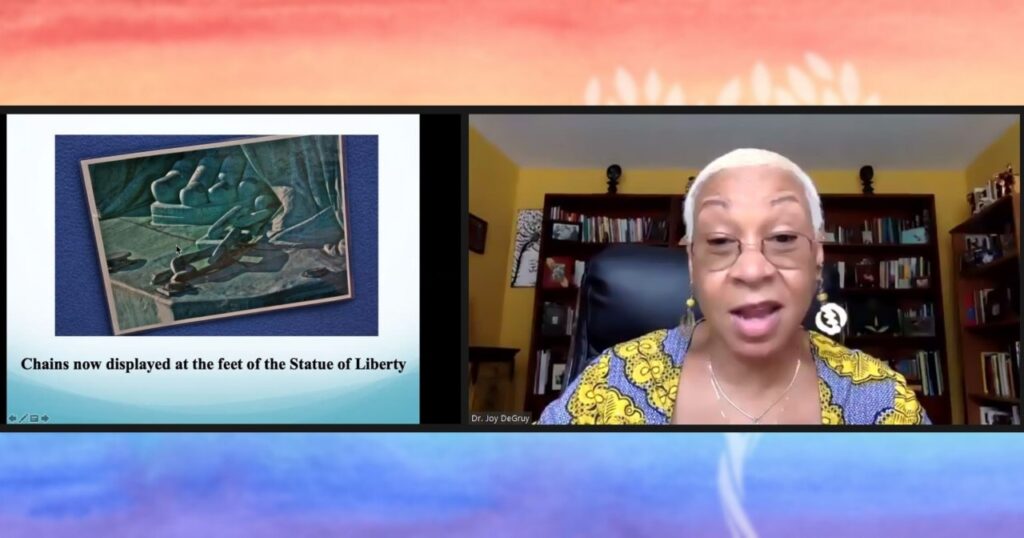

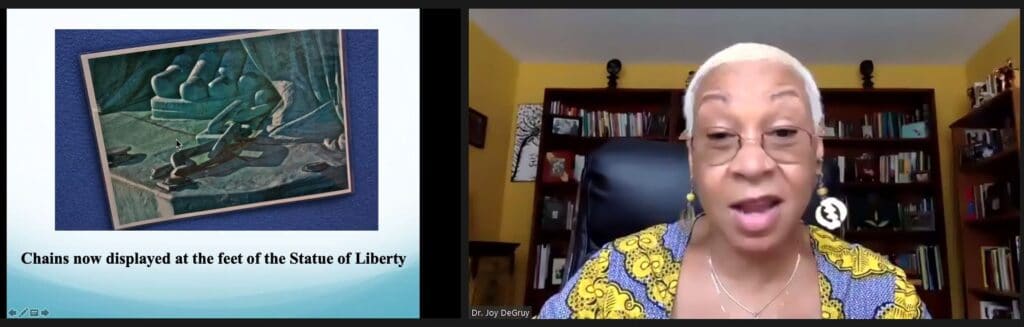

DeGruy then held up another icon of America – the Statue of Liberty – as an example of where the truth has been hidden in plain sight.

She told the story of how she had researched the statue before being taken for a visit, and how she knew that the original French sculpture showed Lady Liberty not with a tablet or book in her left hand – but holding broken chains. It was 1865, and the sculptor wanted the chains to commemorate the end of the Civil War, and of slavery. But the US government did not want that image. The compromise was to show broken chains at the statue’s feet – which are impossible to see due to its position up on a pedestal.

DeGruy said thousands of white people visit the statue and, due to their own ancestors’ arrival via Ellis Island, feel a connection to it. Black people – whose ancestors came as chattel on slave ships – do not.

“Black men and women walk through and feel no connection,” she said. “How much taller would they feel if they saw the chains?”

DeGruy asked officials at the statue’s museum to display a sculpture or photograph that showed the broken chains, offering to pay for it herself. They refused. She then began talking about the chains to every audience that would listen. Eventually, she said, the Department of Interior asked her to come back to New York, apologized to her, and asked her to train the rangers in the story of the chains. They also put on prominent display a picture of the statue’s original design. Then, in 2019, they published a statement: “Lady Liberty was originally designed to celebrate the end of slavery, not the arrival of immigrants.” Ellis Island did not open until six years after the statue was unveiled in 1886, they acknowledge, and the “give me your tired, your poor” poem was not added on a plaque until 1903.

“They have always known this was true,” she said. “They always knew, but they refused to tell the truth. The truth was hidden – in plain sight.”

Tiffany Vail, director of media and communications for the Southern New England Conference, United Church of Christ, is a General Synod Newsroom volunteer.

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More