Seize the moment, weed out racism’s religious roots, activists urge in UCC webinar

This summer’s anti-racist uprisings, together with unjust social systems revealed by the coronavirus pandemic, should prompt the church to “prophesy to ourselves” and weed out white supremacy by its religious roots.

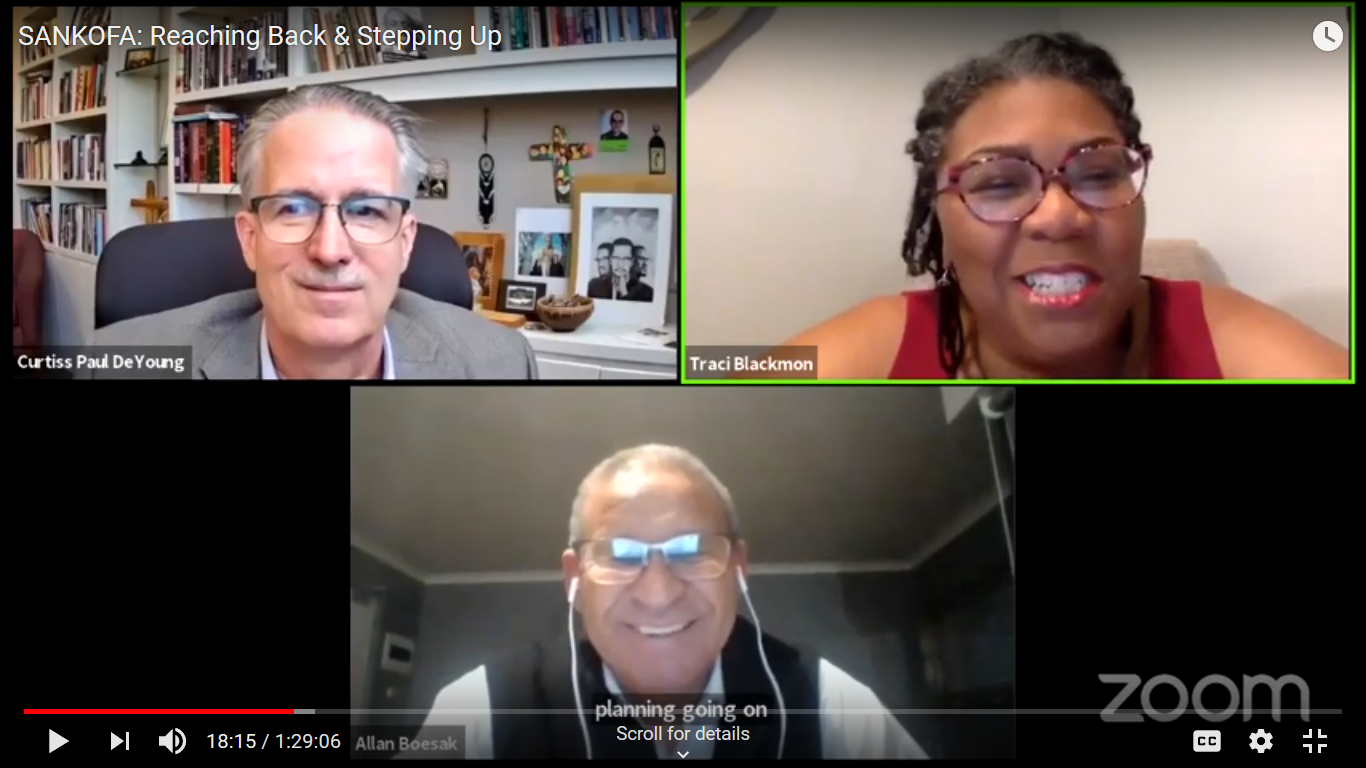

That was a key message from two activists and theologians – one South African, the other American – in a United Church of Christ webinar Aug. 11.

The speakers were the Rev. Allan Boesak, past African National Congress and World Communion of Reformed Churches leader, and the Rev. Curtiss DeYoung, CEO of the Minnesota Council of Churches. They are co-authors of the 2012 book, “Radical Reconciliation: Beyond Political Pietism and Christian Quietism.”

Held live on the webinar platform Zoom and simulcast via YouTube, it was one in a series of conversations with public leaders about how faith informs politics. It was hosted by the Rev. Traci Blackmon, UCC associate general minister. A recording of it can be viewed by clicking here or on either of the images accompanying this article.

Floyd’s death as symbol and spark

Blackmon set the tone by describing the “symbolism, in addition to the actuality, of the death of George Floyd,” the Black man whose May 25 killing at the hands of Minneapolis police prompted worldwide street protests. “He enfleshed so many of the challenges and ills of this time,” Blackmon said. One of them, she said, was that he had COVID-19.

“He had a history of asthma, which is a disease that predisposes people with COVID to have greater consequences of being infected with the virus,” Blackmon said, describing it as just one example of “predisposing factors in black and brown communities around COVID.” Floyd had moved to Minneapolis because he couldn’t find a job elsewhere, “which speaks to the economic distress that we have in our country,” she said. “On top of all of that, his Black skin caused him to be accosted by white police officers and some nonwhite police officers who could not see beyond their concept of his skin.”

“The explosion that took place, of rage and anger and just being tired, built up over many years and many kinds of George Floyd-type situations,” DeYoung said, naming recent killings of Black people in other states as well as in Minneapolis as examples.

DeYoung said the Minnesota faith community is trying to discern “how to seize this moment to set in place the kind of structural change that needs to take place when we address white supremacy in all of its variations – policing being the most public, perhaps, but simply the guardian of a deeper white supremacist system.”

White church’s ‘baked in’ supremacy

The two speakers also described how their backgrounds inform their views of history as it is unfolding today.

DeYoung, from a white U.S. suburb, drew inspiration and mentorship from the Black church and wound up studying theology in African American contexts.

DeYoung, from a white U.S. suburb, drew inspiration and mentorship from the Black church and wound up studying theology in African American contexts.

This summer’s events are “speaking a kind of truth to our nation that we need to hear – a truth that from the very beginnings, this nation was built on white supremacy and a harsh kind of racism,” DeYoung said, with genocide against Indigenous people and enslavement of African people the primary examples.

The U.S. church, he said, is beginning to realize its complicity in this all along. He likened U.S. racism’s roots to those of South African apartheid, which “was first a theological system, then a national system.” “If we look at the kind of Christianity that was brought to these shores, it was a whiten-ized, European, empire form of Christianity,” DeYoung said. “… The framework for our Christian faith in the United States has white supremacy already, as they like to say today, baked into it.”

DeYoung said the white church should recognize its racist traditions and dismantle them. “The very things that we’re calling our nation to do to address white supremacy, we also have to do in the church,” he said. “First, because we’ve been complicit and we need it, and second, if we’re going to have any integrity in having a prophetic voice to the nation, we have to also prophesy to ourselves.”

‘The Jesus we ought to follow’

Boesak grew up in apartheid South Africa and joined religious efforts to oppose it. Insights from that struggle remain relevant today, he said.

In the 1985 Kairos Document, a famous anti-apartheid statement by South African theologians, “we made the distinction between the institutional church and what we then began to call the prophetic church,” also sometimes described as “a restless presence within the church and within society,” Boesak said.

“We also said there are three kinds of theology,” he said. “State theology” tried to create a religious justification for its racist policies and actions. “Church theology” tried to legitimize what the state was doing. According to Kairos, “prophetic theology” is where the authentic church “should be found,” Boesak said. “And that is the church which stands where God stands, which is with the poor and the despised and the marginalized and the excluded.” That form of church was “very much present in the struggle for justice in South Africa” against apartheid.

“You’ve got to be careful what you say when you say you’re a follower of Jesus, because Jesus is about a thousand times more revolutionary than the church can every try to be,” Boesak said. “… The Jesus who is the prophet of Galilee, of occupied Galilee, challenges both the power of the elites in Jerusalem and the power of the Roman empire.” Boesak cited Bible verses (Luke 4:18-20) in which Jesus, at the start of his ministry, proclaims ancient Hebrew values of “good news to the poor,” “release to the captives,” “recovery of sight to the blind” and freedom for the oppressed. “That is the Jesus we ought to follow,” he said.

‘It is a whole system’

The sustained, focused nature of this summer’s uprisings is “one of the things that sort of encourages me and brings joy to my heart,” Boesak said. “I think now people realize, more than a few years ago, that it’s not just about separate cases of police brutality. It is a whole system, not just a system of policing. I think what’s coming under pressure now is the whole racist, capitalist, patriarchalist system that is being enforced on people.

“Not just in the United States, but in the rest of the world, we are seeing more clearly now the work and the workings of empire. And that is why there is this immediate spark, where people across the world felt, ‘What is happening in the United States speaks to us. It is happening here.’”

Boesak said the sustained youth leadership of this summer’s movement “is one of the most encouraging and amazing things for me.” Noting that Black Lives Matter uprisings have occurred several times since 2014, he said, “I’m hoping that the church will be much more involved in this revolution.”

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More