Ministers on state COVID panel want churches to help people accept vaccine

In the fight against COVID-19, churches can play an important role. More than one, in fact.

That’s the view of two United Church of Christ ministers in Detroit who were just appointed to the Protect Michigan Commission. The state’s governor formed it to urge people to get vaccinated.

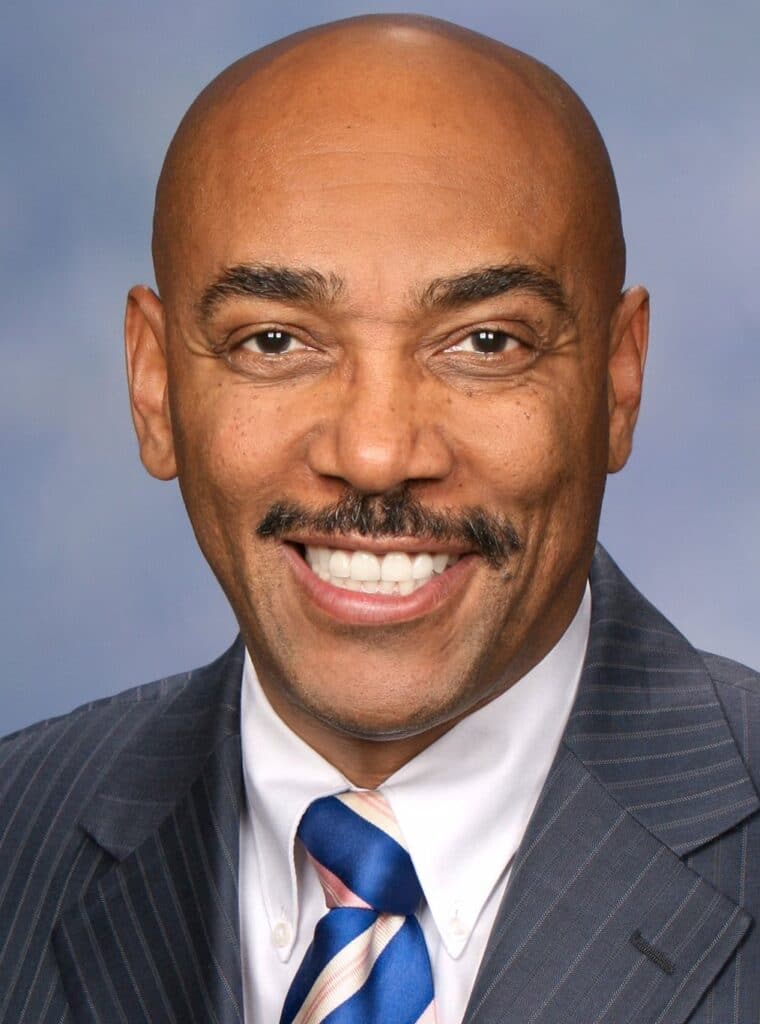

The Rev. James “Jimmy” Womack is a medical doctor. The Rev. Constance “Dr. Coni” Simon has a doctorate in education.

They said public attitudes make promoting the vaccine an urgent matter.

‘Misinformation and apprehension’

“People have been hesitant so far,” Womack said. Some, he said, have real historical reasons. Others may be victims of trumped-up conspiracy theories. Yet others just want to wait and see.

“It’s a commission that had to be formed because there’s so much misinformation and apprehension – and historical things have made people reluctant,” Simon said. “It’s something that’s needed not just in Michigan, but throughout the world.”

Both hope to see churches step up as example setters, myth busters and even vaccination centers.

Sobering acceptance rates

Womack, a retired physician, is assistant minister of health and wellness at Plymouth UCC, an African American church. He also co-pastors St. John St. Luke UCC, which is predominantly white.

He got to know Gov. Gretchen Whitmer when they were state legislators. She was the Senate minority leader; he was a party leader in the House. Because of that relationship, he was invited to apply for Protect Michigan.

At a first meeting on Jan. 25, the 50 members of Whitmer’s commission got facts about the vaccine, plus strategies and tools to get them out in local communities. They also heard sobering findings, Womack said. One was a breakdown by race. State researchers found these percentages of Michiganders were “very likely” to get vaccinated as soon as possible:

- White, 47 percent

- Hispanic, 28 percent

- Black, 25 percent

“That’s very low,” he said.

Why people hesitate

“Hispanic and Black populations have understandable reasons to be paranoid,” Womack said. One of them is the 20th-century Tuskegee Study of syphillis, in which African American men were injected and later denied treatment. Another is the bad experiences many have had with the health care in general. “In the African American community, sometimes you hear, ‘They’re just trying to kill us.'”

But it’s not just people of color who hesitate.

Womack serves on advisory boards for Detroit Medical Center’s four central campuses. He’s noticed that among first responders and hospital employees, “in some scenarios fewer than 50 percent are taking the vaccine.”

“What I’ve witnessed personally is that in some of the federal clinics here, only 45 percent of the employees took the vaccine,” he said.

Conspiracies, rational questions

Womack has heard a range of reasons.

“There are people who believe that anything that came out of the Trump administration is suspect,” he said. “This came together faster than any vaccine; many people are suspicious about the time frame. Also, some people subscribe to misinformation and conspiracy theories: that COVID is not real, that the vaccines will have tags attached to them that will allow the government to monitor them.

“And some people have more rational questions. What are the side effects? What are the long-term effects? How long are you going to be immune? If I’m still going to have to social-distance and wear a mask, why should I get it?”

What will persuade them

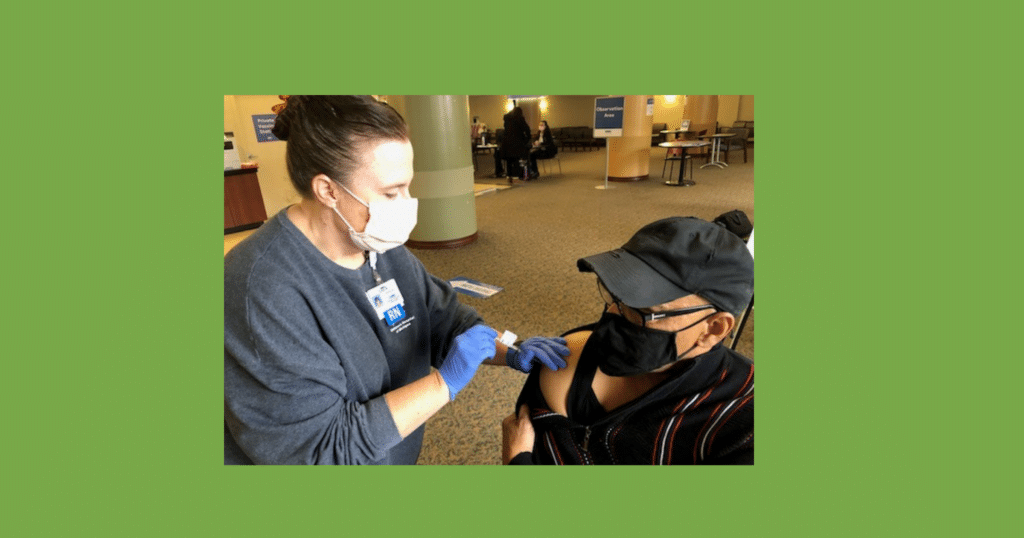

“What I’ve noticed is people 65 years and older are looking to get the vaccine,” Womack said — and that could get the ball rolling. Seeing known people take the shot may persuade others to join in.

“I predict that, in a very short period of time, people are going to be scrambling for the vaccine because they see other people getting it,” Womack said. “People don’t want to be left out.”

And that’s one way the church can help: as a role model.

“If your pastor takes the vaccine, you’re probably more likely to take it than if he or she does not take the vaccine,” he said.

Preaching and modeling

Simon echoed that sentiment. She is minister of Christian education at Fellowship Chapel UCC and an area minister on the staff of the UCC’s Michigan Conference. She also directs the doctor of ministry program at Ecumenical Theological Seminary.

“For the Black community, the pulpit has always been one of the strongest voices,” she said. “The Black church has always been very vocal. This pandemic is a justice issue, a health issue, an economic issue. It has blown up into just about every area of people’s lives.”

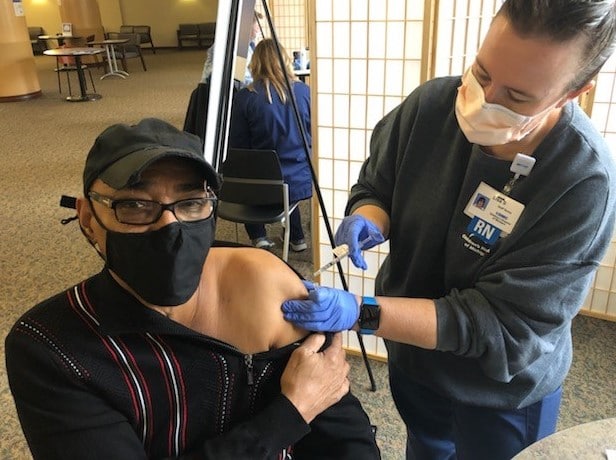

Fellowship’s senior pastor, the Rev. Wendell Anthony, has mentioned the vaccine from the pulpit, she said. “He said, ‘I’m getting my shot.’ He’s encouraging people to get it. Not forcing them, not telling them what to do, but he’s also saying this is a health crisis we’re in.”

Vaccine and the Golden Rule

And Simon described an even deeper educational task for the church. It’s time, she said, to revive the “Golden Rule” — the saying of Jesus, “Do to others as you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12). She recalled a day when it was displayed above chalkboards in schools. Now, she said, many people have never heard of it.

“Not only is it our work to teach people the truth of what’s going on with the virus, but to teach people how to be kind and gentle and how to care about people beyond themselves. Living into being your neighbor’s keeper. Love your neighbor as yourself.”

That’s the point of COVID prevention, including vaccination, she said: protecting not just oneself, but others. “The average person might say, ‘I’m not going to take this. I don’t have to.’ But we need to look at it through a larger lens. It can’t be, ‘I’m OK so I don’t care.'”

The task is to bring people “back to being more humane,” Simon said. “It’s truth-telling — truth-telling for the sake of love.”

What else churches can do

Beyond modeling and teaching, Womack and Simon suggested ways churches can aid vaccination in their communities:

- Become a COVID testing and/or vaccination center. Start by checking with your local health department to see if that’s a need.

- Create a volunteer team to track where vaccines are offered and keep members and neighbors updated.

- Reactivate networks and strategies from last year’s “get out the vote” efforts to get people out to get shots.

- Get vaccine information out through the church’s existing food programs and other outreach ministries.

“Churches are critical, in my opinion, for the administration of the vaccine,” Womack said — and for getting to the most vulnerable people in the community. “When we talk about being judged for that which we do for the least of these — here you go.”

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More