Entrepreneurs in ministry get creative with local spaces

In Houston, Vanessa Monroe wants to “disrupt division” by inviting neighbors into a quiet retreat space that has kept them out for years. In rural Mississippi, Art Cribbs wants to teach financial health and a global worldview to local people on the campus of a historic Black school.

They’re among seven “spiritual entrepreneurs” who are finding support – and supporting each other – in the United Church of Christ’s 2022 Adese Fellowship program. In various ways, each of them is using physical space creatively to lift up a surrounding community.

Run by the Church Building & Loan Fund with support from other national UCC ministries, Adese is a yearlong journey. Through retreats, video conferences and site visits, participants “gain clarity about themselves and their venture, prototyping and testing their concept, and building a team,” according to the program’s website.

Theological study is also a core part of the curriculum. “Adese embraces the idea that whatever ignites faith, eliminates poverty and redeems creation is what the mission of the church is all about,” said the Rev. Patrick Duggan, CB&LF executive director.

A ‘seasoned’ class

For the first time since Adese started in 2017, all current participants are UCC members – and all are well into their careers. They gathered online for their first retreat at the end of January.

Besides Monroe and Cribbs, whose visions are described below, the Class of 2022 and their projects are:

- Karen Beiber, Lovingston, Va. Create a residential setting to help single mothers reenter the community after incarceration.

- The Rev. Lee Gagen, Framingham, Mass. Connect the community surrounding the offices of the UCC’s Southern New England Conference with the resources and work of the Conference.

- The Rev. Jesse Knox, Chicago. Restore a former parsonage to house women veterans and their children; connect with local institutions in a strategy to support them.

- Vicki McGaw, Middleburg Heights, Ohio. Buy and renovate a multi-unit building to house either homeless veterans or refugees at sliding-scale rents.

- The Rev. George Miller, Sebring, Fla. Fight hunger, loneliness and depression by gathering people to grown their own food, aided by an ADA-accessible community garden and refrigerator.

“These experienced individuals are embarking on new journeys using their skills from their seasoned ministry experiences,” said CB&LF Strategic Programs Administrator Melina Higbee. “All of their ventures are unusually intertwined and will compliment each other well. I’m excited to see how the ventures unfold and impact their communities.”

Church on a journey

The Rev. Vanessa Monroe is pastor of Bethel UCC, which took a bold step in 2017. After a process of self-study, using the UCC’s New Beginnings curriculum, the church left the northwest Houston neighborhood where it had been for 101 years.

Bethel sold its building and nested with another church for a year. In 2018 it bought a new home in southwest Houston: the seven-acre Journey Conference and Retreat Center. It’s a quiet space in a busy urban landscape of homes, businesses and vacant lots.

“Once one drives onto the property, there is the definite feeling that you are away and enveloped by something very special,” Monroe said. It has trails, gardens, water features and indoor spaces. She envisions the campus as a place of rest and healing in a neighborhood rich in African American culture but with “not a lot of financial resources.” “It’s a vibrant area where there is still a lot of need,” she said.

Fences and neighbors

But there’s a problem. The church’s property is a mystery to its neighbors. And the tall, wooden privacy fence surrounding the property is just one reason for that.

“People in the community rarely tread behind the fence,” Monroe said. “Initially, the property was a Buddhist retreat center, then a Catholic center. Neither previous faith community invited the people of the neighborhood to the center. Neither engaged in cross-cultural relationships or pluralistic initiatives.”

As a result, she said, when people first stepped onto the grounds – invited by the church during a neighborhood tour – they said things like, “We had no idea this was here.” And that reaction was tinged with suspicion. When the leader of a local school came behind the fence for a visit, her phone kept ringing. “My sister keeps calling me,” she told Monroe. “She’s worried about me because she doesn’t know what’s back here.”

‘Wellness and refuge’

That’s the challenge Monroe is working on during her Adese year. “I seek to disrupt the division,” she said. “I seek to provide space for people in the community to rest.”

She and the church want to create a campus devoted to wellness. And in a community with a large population of African Americans, who suffer disproportionately from high blood pressure and heart disease, “this really is about survival,” Monroe said.

“There are some things we can do to mitigate this,” she said. “There’s lots of literature that says restorative work can go a long way: prayer, mindfulness, rest, exercise – practices that help us live healthier, more resilient lives. We want to, with the community, create this place of wellness and refuge, a place where our community can breathe.

“And I mean that literally and figuratively. Where they can come behind the gates and participate in a yoga class, or walk the gardens, or pick the greens from our garden, or take a class that teaches about imaginative breath work or meditation or silence. Like Howard Thurman describes – a place ‘where one can center down.’

“That is what Adese is helping me both fully imagine and create.”

‘God is in this’

For that vision, Bethel will need financial resources “to pull the talent necessary to help create and to offer these services,” Monroe said. “Some of that may be in the community, some of it may be outside of the community.” And she wants to avoid creating a brand-new barrier: the programs must be affordable. “We need resources so that we can offer sliding-scale or discounted rates.”

“Adese is definitely helping me with that, to understand what kind of resources are available who believes in this kind of work and will help fund it,” she said. “And how to find those people – how to share our story in a way that allows them to connect with the work that we’re doing. And to ground our work and frame our work theologically: yes, God is in this, God is for this, God is with us.”

Monroe said hearing her Adese classmates describe “so many really brave ideas” energized her. “To hear the passion, how they came to these projects – this is authentic ministry that God is showing us in response to the world,” she said. “It’s a pretty wonderful place to be and to work this out together.”

Reviving a school

In a career spanning radio and TV journalism, nonprofit leadership, and UCC work in national, global and local settings, the Rev. Arthur Lawrence Cribbs Jr. has lived a mobile life. His usual home is in Los Angeles. He’s currently serving as interim minister at Little River UCC in Annandale, Va.

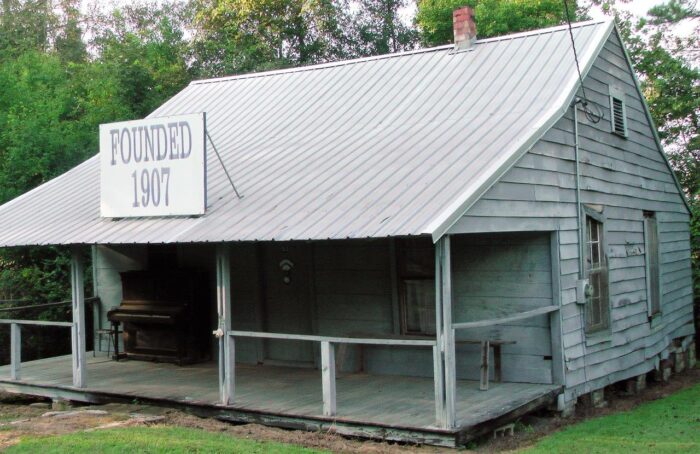

And he has roots in rural Prentiss, Miss. There, his extended-family ancestors were founders Prentiss Normal and Industrial Institute, later simply Prentiss Institute. From 1907 until it closed in 1989, generations of local people studied there.

Now he belongs to the recently formed Prentiss Institute Partnership Team. Together with trustees of the 500-acre campus, its 36 members are working on a comeback plan. They want to make it a center of learning again. Prentiss is in “one of the poorest counties in the country,” he said, “and it’s about 60 percent African American.”

A financial empowerment class for 50 to 75 local residents is scheduled to kick off the learning revival. Its theme: “You work for money. Let money work for you.” Professional financial advisors, Cribbs said, will “teach poor and low-income workers how to save and invest their money as the foundation for a more secure future.”

‘A heavier lift’

People who live in and around Prentiss need to know they can start that process, even with modest assets, he said. “If you have a home, you have assets that can create an economic future for you. People don’t realize that. They’ve been beaten over the head to say you’re poor, you’re impoverished.”

And therein lies a challenge no smaller than what the founders of Prentiss faced during segregation.

“In reality, it’s a heavier lift in the 21st century than it was in the 20th,” Cribbs said. “We have deep rehabilitation work to do, where people have been labeled, denied, incarcerated, addicted. In 1907, it was an act of inspiration and opportunity. Now we have to undo so much in terms of people’s life experiences.

“We have drug addiction. We have criminal records – things that take people out of competing with others. We have to help people see themselves with other imagery: ‘My past experience doesn’t define the totality of who I am.’

“We need to take people as they are and affirm them in God’s image. That’s a very different perspective than we just need to get people educated so they can go into the world.”

‘Think bigger’

And going into the world – in a big way – is ultimately part of Cribbs’ vision.

He foresees – someday – an 18-month “global citizens academy” at Prentiss that would “prepare people to be culturally competent to go anywhere in the world and be an asset wherever wherever they land.” It’s inspired by his work in the 1980s with the United Church Board for World Ministries, a forerunner of today’s Wider Church Ministries and Global Ministries. “That experience cracked my world wide open,” he said – and there’s no reason people in Central Mississippi can’t take their talents around the globe, too. “People are more mobile today than in 1907,” he said. “They can see themselves in a global context. The whole world is open.”

Cribbs said Adese is already helping him hone his vision and an appeal for financial support for Prentiss. “My takeaway from just that first two-day gathering is to, one, articulate your story clearly, passionately and inspire others to be engaged in the work you’re doing,” he said. “And, two, begin to pitch your story, tell your story, so that you can attract the funding you’re looking for.”

He has a head start. In 2020, he narrated a video about the school’s history, its impact on past students’ lives and its future possibilities. Now Adese is inspiring him to embrace the scale of whatever may come after that initial financial wellness class – which he hopes will take place as soon as the COVID-19 pandemic lifts.

Cribbs said he took this message from Adese’s January retreat: “Think bigger. Think forward. Don’t be shy about the good work you’re doing and the impact you’re having on others. Tell the story with passion. Be compelling. Let others know that the work that you’re doing has an impact on people’s lives.”

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More