As hymnal turns 25 and National Youth Event nears, words are still a matter of justice

Music and language at this month’s National Youth Event are carrying forward a longtime United Church of Christ belief that the words we use to describe God and people are a matter of justice and inclusion – a movement that took a huge step 25 years ago.

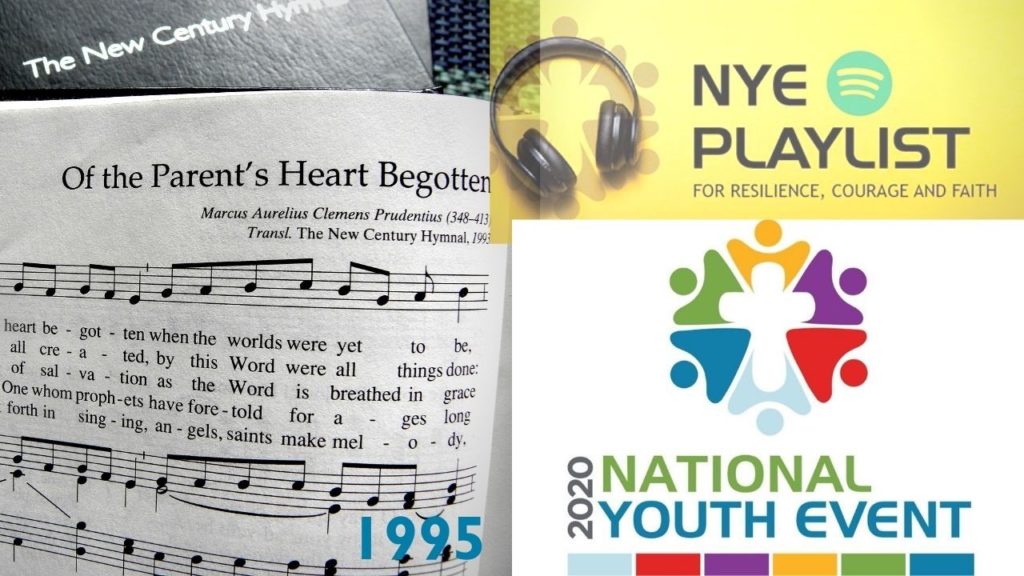

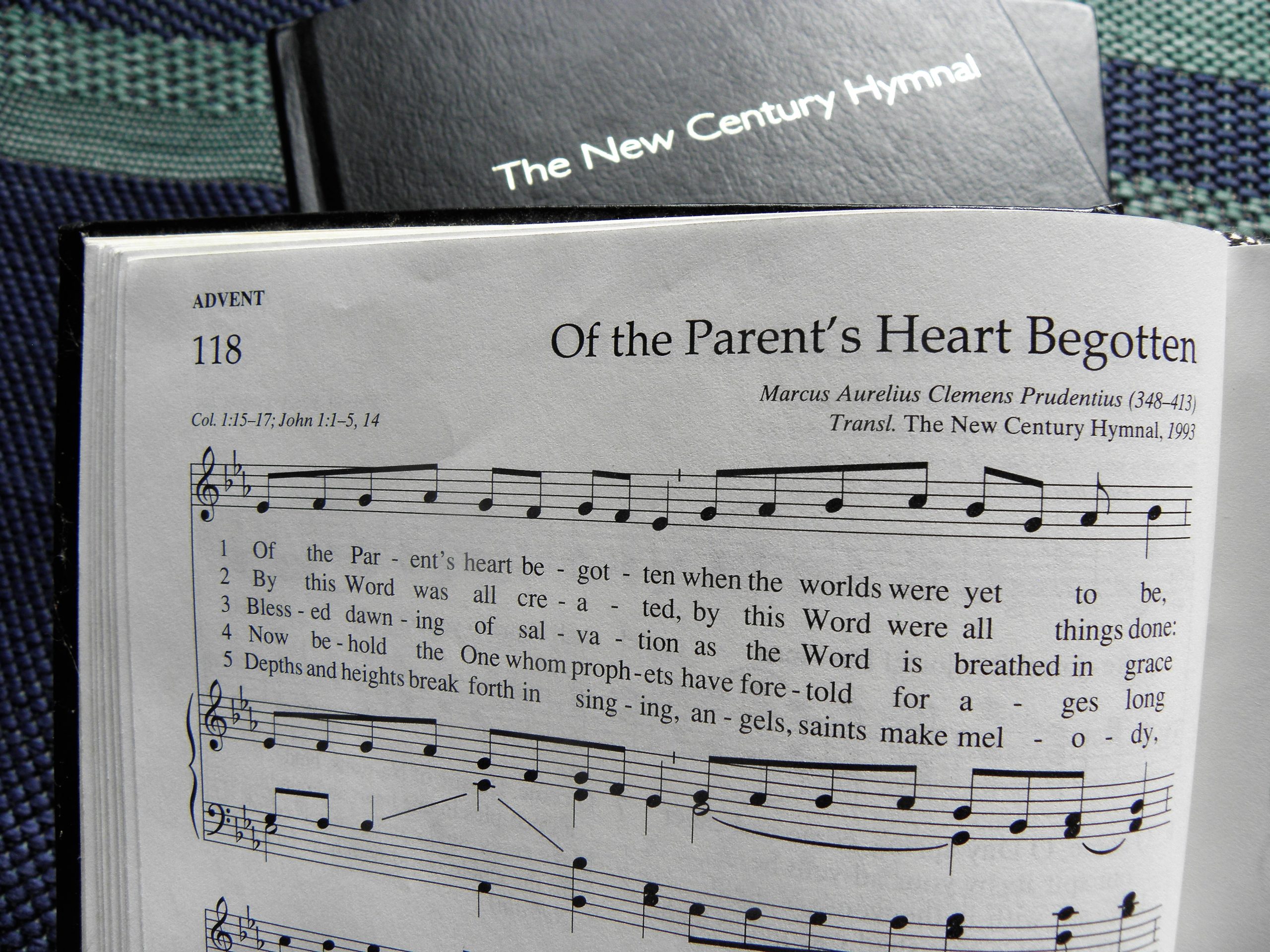

The New Century Hymnal, dedicated at General Synod on July 2, 1995, broke new ground. It included works from racial and ethnic traditions not seen in previous UCC hymn books. And it balanced masculine images with feminine and other expansive ones. It did that by altering existing hymn texts as well as introducing new hymns and recovering ancient ones. This attracted controversy as well as praise, from inside and outside the UCC.

The New Century Hymnal, dedicated at General Synod on July 2, 1995, broke new ground. It included works from racial and ethnic traditions not seen in previous UCC hymn books. And it balanced masculine images with feminine and other expansive ones. It did that by altering existing hymn texts as well as introducing new hymns and recovering ancient ones. This attracted controversy as well as praise, from inside and outside the UCC.

The tradition is still evolving today. Leaders of NYE, which has moved online this summer and will culminate July 25—26, are focused on a range of justice concerns. Among them are language that honors transgender, nonbinary and other identities – issues that weren’t yet on the agenda for the New Century committee in the early 1990s.

“The New Century Hymnal remains a theologically progressive work and it is foundational for our denomination,” said the Rev. Tracy Howe Wispelwey of the Justice and Local Church Ministries staff, who helped write an “Inclusive Language, Antiracist and Just Peace Lyric and Music Policy” – just for NYE, not as a wider denominational policy. Since 1995, she said, the UCC has “grown that much more in how we can honor and dignify the God-Image in people, and, in doing so, grow in words and the expression of our worship to the Triune God.

“A clear example of this is how the NCH so beautifully expanded us into gender-neutral and feminine imagery of God, but is insufficient in queer imagery and nonbinary language, which is different than gender-neutral.”

Long-standing UCC desire

Shapers of contemporary guidelines can expect both support and struggle, if the experience of 25 years ago is any indication.

Many UCC people were asking for inclusive-language resources long before The New Century Hymnal arrived, as the hymnal’s own introduction points out. In it, the chair of the committee that helped shape the hymnal, Rev. James Crawford, then senior minister of Boston’s Old South Church, described extensive research – including 35 public forums – to learn what local churches wanted.

Many UCC people were asking for inclusive-language resources long before The New Century Hymnal arrived, as the hymnal’s own introduction points out. In it, the chair of the committee that helped shape the hymnal, Rev. James Crawford, then senior minister of Boston’s Old South Church, described extensive research – including 35 public forums – to learn what local churches wanted.

“From thousands of responses,” he wrote, “… the majority of congregations that would buy hymnals in the next decade seek, first, new music, and second, inclusive metaphors for God and the human community. These findings confirmed the vision of General Synod in 1977 for an inclusive-language hymnal, and they were the foundation for the work of the advisory Hymnal Committee.”

The New Century Hymnal has, in fact, sold thousands of copies a year since 1995 – 448,499 in total as of June 30, 2020, to be exact.

Taking inclusiveness literally

But resistance emerged rapidly, too. A Newsweek writer in 1995 accused the hymnal of promoting a “new religion.” One local UCC church proclaimed the new book to be “of the devil,” said its editor, Arthur Clyde, now on the music staff of Union Congregational UCC, St. Louis Park, Minn. More common, he said, was the reaction of an Iowa congregation that bought the new hymnal but kept its old Pilgrim Hymnals in the pews, too, as people adjusted.

There were those who felt New Century should have been less aggressive in eliminating masculine metaphors that were so deeply rooted in hymn-singers’ memorization banks. But the hymnal committee – working from agreed-upon theological guidelines – came to an important turning point as the hymnal was being developed, Clyde told scholar Jim Coppoc for a recent paper at United Theological Seminary.

“It was captured in a heated conversation of the committee over a beloved hymn that had some archaic words that an African American member of the committee said also had some racial overtones. The reaction of another member of the committee was that a hymnal should be like a museum and it could contain all the biases of the church throughout the ages because they are part of our history. … The African American member responded, saying, ‘So you’d like us to walk through your museum and sing a little bit of racism, and a little bit of sexism, and a little bit of oppression? And where do you draw the line?’

“The outcome was to hold all the hymns to the same standard,” Clyde said, resulting in “the most even and consistent approach to language of any hymnal yet published. Rather than choosing to present only new hymns in inclusive language, we took the General Synod request for an inclusive hymnal literally and moved forward with revisions to present the hymns of other ages with their theology and beauty but without some of the biases of the time in which they were written.”

Reviving ancient insights

“It isn’t thought of, I think, now, as way out or far out,” said the Rev. Ansley Coe Throckmorton, who headed the Division of Education and Publication of the United Church Board for Homeland Ministries, which was in charge of the hymnal’s publication. “Where it’s used, it’s used happily.”

“We concentrated so hard on gender,” said Throckmorton, now retired and living in Bangor, Maine, where she belongs to Hammond Street Congregational Church, UCC. “Everybody on the committee was conscious of all kinds of inclusiveness, including racial. It was always part of the picture. Because gender was so controversial, that got all the attention. But the racial part was always there.”

Inclusivity was not the only way in which New Century was “ahead of the times,” said the Rev. Thomas Dipko, executive vice president of UCBHM at the time of its publication and author of its foreword. Now retired and living in San Francisco, he is a “non-resident member” of Christ United Church in Olmsted Falls, Ohio. He mentioned, for example, the hymnal’s “integration of hymns and scripture through its close alignment with the Revised Common Lectionary.”

Inclusivity was not the only way in which New Century was “ahead of the times,” said the Rev. Thomas Dipko, executive vice president of UCBHM at the time of its publication and author of its foreword. Now retired and living in San Francisco, he is a “non-resident member” of Christ United Church in Olmsted Falls, Ohio. He mentioned, for example, the hymnal’s “integration of hymns and scripture through its close alignment with the Revised Common Lectionary.”

Through historical research, New Century was even able to eliminate masculine language that wasn’t in original texts but that had been added over time. One example, Dipko said, is the hymn “Of the Parent’s Heart Begotten,” which correctly translates the ancient Latin. All other modern hymnals use “Father’s” instead of “Parent’s,” he said.

“Voices in other denominations that initially doubted the wisdom of decisions that shaped our hymnal are now earnestly seeking ways to go and do likewise,” Dipko said.

‘Whether representation is enough’

“I’ve been in meetings with people from the United Kingdom who say ‘Wow, you have The New Century Hymnal – it’s so subversive,” said the Rev. Sue Blain, the UCC’s current minister for worship and gospel arts. “And it really is. It tried to subvert the patriarchy.” She remembered how welcome the hymnal was to worship leaders in the 1990s, who, like her, had been cobbling together inclusive resources on their own.

“Now other issues of justice really are coming to the forefront,” she said, including “the wider conversation about racial justice.” Building on the work of 25 years go – when six of the 15 people serving on the hymnal committee or editorial panel were people of color – leaders today are raising “questions about whether representation is enough,” Blain said. She’s seeing that not only in the UCC – where she has designed and coordinated General Synod worship for years – but in the work of partners such as the United Church of Canada, which invited her onto one of its subcommittees for a hymnal it hopes to publish in 2025.

“Racial justice is still and always has been a really vital issue for us,” Blain said. “But the questions of who’s at the table, what does representation mean, is representation a good thing or is there a more integral way to work – those are more the questions that are coming into being in thinking through hymnody.”

“We still get mail from time to time complaining about The New Century Hymnal, complaining about awful it is, but less and less,” Blain said. “And there are also folks who look at it as the last word, but it in fact it’s the first word. The last word in one conversation, but the first word in another.”

In NYE, that continuing conversation is evident in things like the “pillars” that frame the event’s programming and in its language guidelines that inform, among other things, an NYE playlist posted on Spotify this spring.

In NYE, that continuing conversation is evident in things like the “pillars” that frame the event’s programming and in its language guidelines that inform, among other things, an NYE playlist posted on Spotify this spring.

‘Encourage the poets and musicians’

“I developed a lyric and worship language policy for NYE that sought to build upon the inclusive language policies of past events and demonstrate a faithfulness to the Gospel as we see it alive in our world today,” said Wispelwey, minister of congregational and community engagement. “In addition to inclusive language, it spoke about antiracist and decolonizing language. Music and lyrics are full of intersectional issues because they carry theological language and music is a cultural expression.

“There cannot be a movement for gender-expansive language for God that does not acknowledge whiteness, racism and inequity in the church. There cannot be tokenism and racial representation without a commitment to equity and racial justice. We need more than gender-neutral language. We need language that affirms the God-Image of queer and trans people.”

The playlist, for example, resulted from a “long, collaborative and thoughtful process.” The resulting mix, she said, “is full of inclusive language and there are a diverse group of artists on it, but it took about four months to put together!”

“Hymns were actually very tricky because there are so many different versions out there and some of the artists and communities putting out recordings of them are not affirming of the God-Image in LGBTQ people, or even the full strength and capacity of women,” Wispelwey said. “There are some horribly problematic and violent theologies in the world and in music, so all artists on the playlist were vetted to ensure, as much as we can, we are exposing youth to life-giving, humanity-affirming people.”

“The creativity of each new generation, it seems to me, is exponentially increased by advances in electronic communication,” Dipko said. “If we are wise, we will encourage the poets and musicians among us to immerse themselves in the Christian message in all its ecumenical riches, and turn them loose to imagine lyrics and music that reach for the depths of our hearts and for the stars. The future is already within them. As an octogenarian eager to see their contributions, I wish them godspeed.”

Related News

A Prophetic Call for Justice and Peace in Palestine

The executive leaders of the United Church of Christ have issued the following statement...

Read More‘Love is Greater Than Fear’: Regional Youth Events get to the heart of gospel message

United Church of Christ teens attending this summer’s Regional Youth Events (RYE) are...

Read MoreUCC desk calendars available to order now

Prepare for your day, month and year with the United Church of Christ desk calendar —...

Read More