Displaced, But Not Forgotten in South Sudan

WHEN HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF SOUTH SUDANESE ARE FORCED TO FLEE THEIR HOMES, IMA MEETS THEIR MEDICAL NEEDS WHERE THEY ARE.

The town of Kodok sits on the western side of the Nile River in the far north of South Sudan. The “western side” is important. The eastern side, from the town of Malakal to the northern border has experienced endless explosions of violence since December 2013, causing a massive movement of people away from the area. Once South Sudan’s second largest city and a mix of various ethnicities, Malakal is now a shattered, burned, and mostly abandoned shell of a town.[1] Its residents have scattered to safety among their own ethnic groups, and this western side of the river offers a small measure of security for upwards of a hundred thousand displaced people.

One of the greatest issues that arises when a massive movement of people occurs is access to health facilities; any services still available are now stretched far beyond their limits. With emergency funding from the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA), IMA World Health stepped into the aftermath of the crisis to set up and manage multiple mobile clinics for both the displaced and the host communities.

300 Meters

The MAF Cessna Caravan, loaded to the max with medicine and medical supplies, takes a little over two hours to reach Kodok from Juba. The plane is filled with fuel for a round-trip as there are no locations anywhere in the north to re-fuel. Pilot Reinier Kwantes plans the final bit of his route to by-pass Malakal airspace as he descends. He can’t take the risk of getting shot.

Once he crosses the Nile River, he eases down to take a closer look at the 950-meter airstrip, making a low pass. IMA staff warned earlier that it had rained two days before, and this strip can’t handle much rain. It’s made from the dreaded black cotton soil, which turns into sticky glue when it becomes saturated. Reinier estimates that a strip of mud begins 400-meters in. The airstrip is wide, though, and there’s room to spare on the right of the mud patch if he needs more. It will be easy enough to take off as well with an empty load.

He lands in 300 meters, braking hard. It was a good call. The IMA clinics need this cargo.

Donkeys, Quads, Tractors, and Canoes

It’s crystal clear that getting around this area is difficult, especially in the rainy season. Four donkey carts arrive to pick up the cargo. IMA Medical Supervisor, Dr. Oleny Amum, and Field Operations Coordinator, Serunkuma Luigi Adwok, arrive on a quad bike. The cargo includes malaria rapid tests and anti-malaria injectables, external and topical drugs, oral and injectable medicine, IVs, and syringes. Oleny and Luigi are responsible for making sure the cargo makes it to all the IMA medical clinics in the region.

This is the difficult part.

“These are not for Kodok alone,” Dr. Oleny explains. “It’s for all mobile clinics. We distribute the medicines equally. We divide them here in Kodok, and then transport them to the respective areas – in Luul, Ogot, Wau Shilluk, and Wau Primary Health Care Center. They are too far away. We take them by tractors, sometimes by the river, by canoes. Sometimes we go by quad bike, which takes three hours to the next clinic. By canoe it takes almost two days to Wau Shilluk. They have no other way to get the medicines.”

Just getting to the Kodok mobile clinic on the outskirts of town is tricky. Luigi drives while Oleny sits on the back. Once off the dirt road, it’s wet, slippery mud the rest of the way. Oleny points to possible less-muddy routes as they make their way to the small enclave of white tents and huts that make up the mobile clinic.

Our Level Best

The number of displaced people is staggering. In this region alone, an estimated 150,000 people fled their homes and few have settled permanently. Through the mobile clinics, IMA provides emergency and primary health care services to approximately 128,000 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from Upper Nile State, and emergency nutritional needs to approximately 202,500 IDPs and host community members. Between February and September 2015, the clinics in Upper Nile State saw a total of 52,534 patients and distributed approximately two to three tons of medical supplies each quarter.

“We are facing many difficulties to operate here,” Luigi says, “like the accessibility to the clinic sites after we receive the drugs, especially in the rainy season. After the crisis there was a shortage of many things for us to survive here, but we are struggling to do our level best to ensure that the health services reach the internally displaced and host community as well.”

Serving to the End

In Kodok alone, there are an estimated 35,000 IDPs. Luigi and Oleny say they receive an average of 110 patients per day at the Kodok mobile clinic. The staff is part of the community of displaced people, having fled their homes and jobs in Malakal. By hiring and training staff who are themselves IDPs, IMA gives health workers a chance to serve their own communities.

“We depend on the medicine from Juba,” Oleny says. “Since we started the clinics, MAF has been transporting the drugs and all things we need in the facilities. It is a great job and great role MAF is playing. It is what we need, and we are still going ahead and giving the service to the community.”

IMA hopes to continue serving this population until the need no longer exists, and MAF will be in South Sudan, continuing to help.

Related News

Operation Cacti: Compassionate Care for Children

As Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents make devastating sweeps through cities and...

Read MoreIntroducing Megan: UCC’s New Minister for Refugee and Migration Services

The United Church of Christ is pleased to welcome Megan as the new Minister for Refugee and...

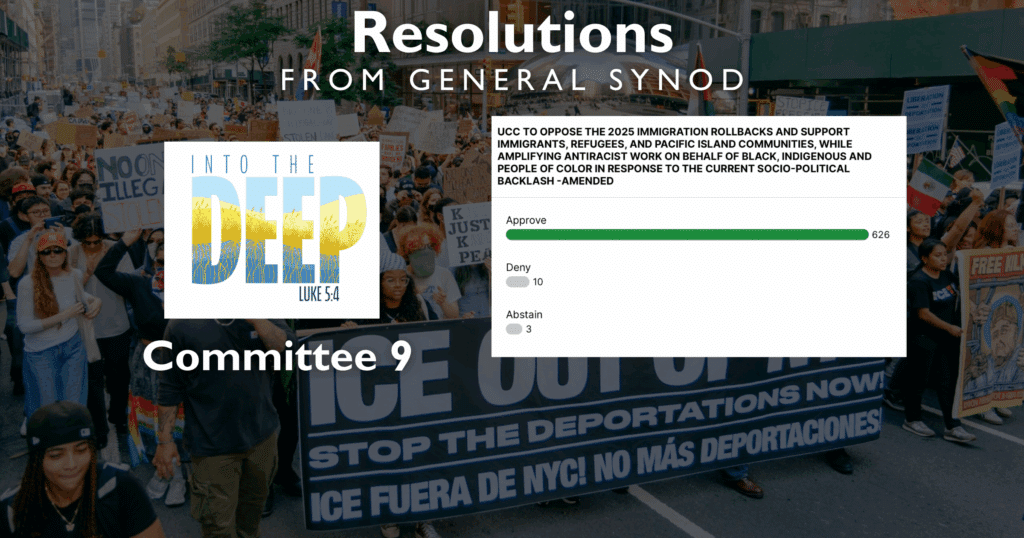

Read MoreResolution Opposing Immigration Policies Passes

Delegates to General Synod 35 overwhelmingly approved an emergency resolution that opposes...

Read More